Civil Ceremonies is a founder member of the Wedding Celebrancy Commission and the commission now…

Anecdotes in Funeral Tributes

Those stories that bereaved families tell you as a funeral celebrant and you re-tell in such a way that they vividly recall the person who has died, if only for a moment. At the time of their death, their ‘story’ needs to be as alive as it can be. They are important, such stories, for that very reason.

Just for a while, they allow those listening to experience an emotion other than grief as they remember something amusing or typical of the person. It shows them that it is possible, if only for a moment. The celebrant’s hope is that they will go on recalling and sharing memories after the ceremony and in the weeks and months following.

Worries about telling anecdotes include being viewed as ‘over the top’ or ‘over dramatic’ or the story falling flat and no-one smiling at it or being seen as inappropriate for a funeral. Despite these concerns I believe it is well worth working to get these stories told well.

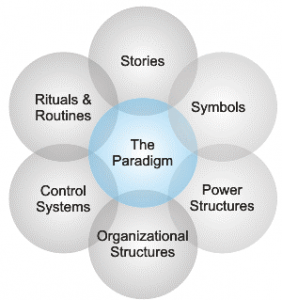

The first step is getting the stories, which usually happens at the meeting with the family. The stories to seek are the ones from the ‘cultural web’ of the family; every family has its rituals and routines – its symbols and power structures. We just tend not to think of it that way very often.

The Cultural Web

In your own family you will know exactly the stories that get re-told every time the family meets up at Christmas, weddings and funerals! Don’t force it, it’s a conversation, gently nudge and the stories will eventually tumble out.

To start with, get the ‘landscape’ of the story. Images are fundamental to any story and you have to see it before you can write it and tell it. Where was the story played out? Ask enough questions to get the landscape and paint it in your own head so you can set the scene.

Then there is context. People need to understand the story. Tell them the place and the time it took place.Get the geography. Where are you? Parachute yourself into the landscape and clarify that you have it right with checking questions.

Most importantly, what is the story? Establish which parts of the story are crucial. Youdon’t have much time so you need the key facts and the point of the story to be clear. Make it easy to understand the top line of the story by getting the right sequence of event.

Get the detail. The detail paints the picture and gives you the adjectives you need. The difference between a ‘huge’ wave and ‘a wave’ that knocked her over – the difference between a ‘teeny, miniscule cut on her finger‘ and a ‘small cut on her finger’

Get the contrasts. Look for opposites, ‘up and down’, ‘huge and small’, ‘light and dark’. Put these into the story to make it more interesting, to embellish, as long as you don’t become inaccurate, as someone will notice if you get it wrong.

It can be hard to decide whether to use a particular story.

Deciding whether to use a particular story is difficult. Is it appropriate? Only you can tell this so trust your gut instinct on it. You can ‘read’ the family and will know if it is appropriate to use the story.

Dodgy language. There may be a swear word in the punch line, where do you draw the line on what you will say? Appropriateness can be an issue. What words will you say, what won’t you? Know when to cross or not cross your own personal line, again your own gut instinct is the best judge.

Why does this story matter? The most important question of all is what does this story demonstrate about the person who has died? If nothing then don’t use it. Use it when it tells you something ‘deep’ about the person, whothey really were, demonstrates their quality and attributes, or a fault. Don’t worry about using a good story to demonstrate a fault.

If you use anecdotes well they will lift the tribute and you will see the memory of the story reflected in the faces of those listening.